A shortage of aluminum due to declining demand in China and elsewhere and rising supplies will undermine prices for the metal used in the transportation, packaging and construction industries, likely through the end of 2023. With shrinking manufacturing activity in China, the United States and Europe, the outlook for industrial metal consumption appears sluggish.

A shortage of aluminum due to declining demand in China and elsewhere and rising supplies will undermine prices for the metal used in the transportation, packaging and construction industries, likely through the end of 2023. With shrinking manufacturing activity in China, the United States and Europe, the outlook for industrial metal consumption appears sluggish.

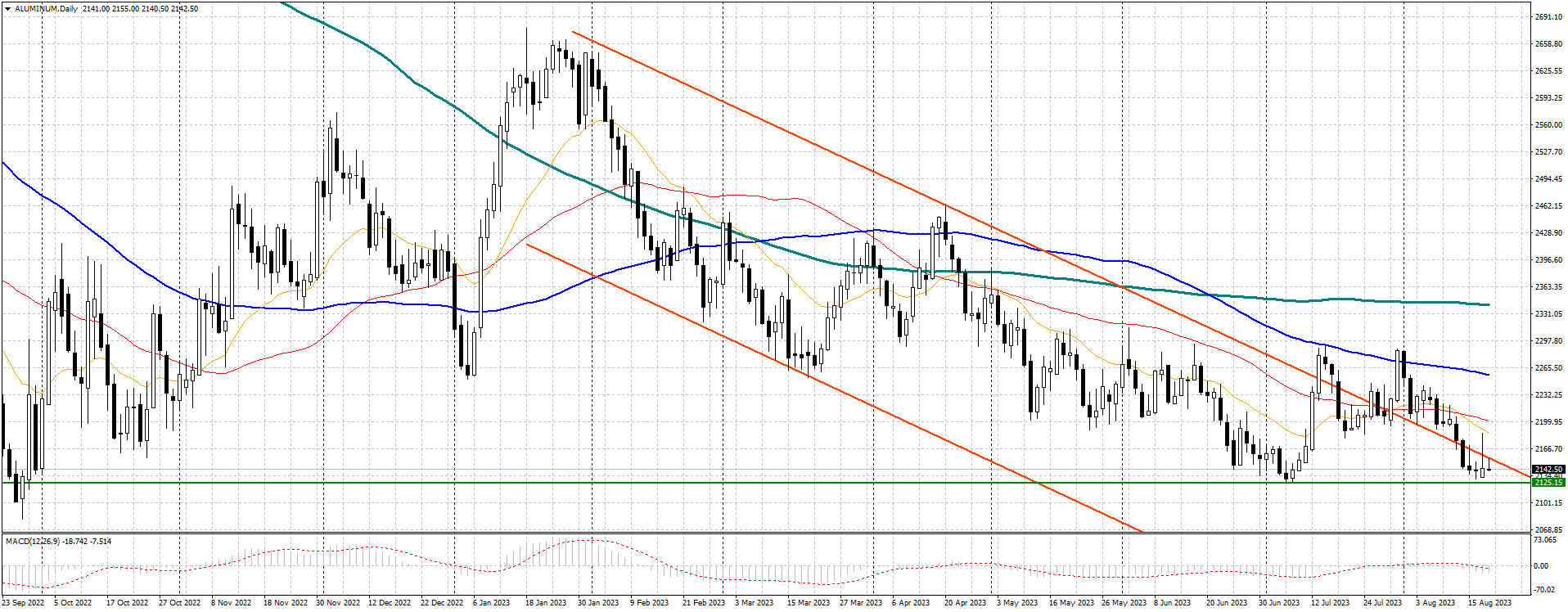

Benchmark aluminum on the London Metal Exchange (LME) fell Wednesday to a five-week low of 2,134 tons, down 20 percent since mid-July. The demand side has taken over in terms of aluminum weakness. It is not just China, but the whole world.

Hopes that Chinese demand would take off in January after China abandoned its strict “zero-COVID” policy have been dashed, and while the country’s government has talked about stimulus, the lack of concrete details is a headwind.

Also undermining prices is China’s aluminum production, which accounts for 60 percent of global output, estimated at about 70 million tons this year, and which has picked up along with improved hydropower supplies in Yunnan province.

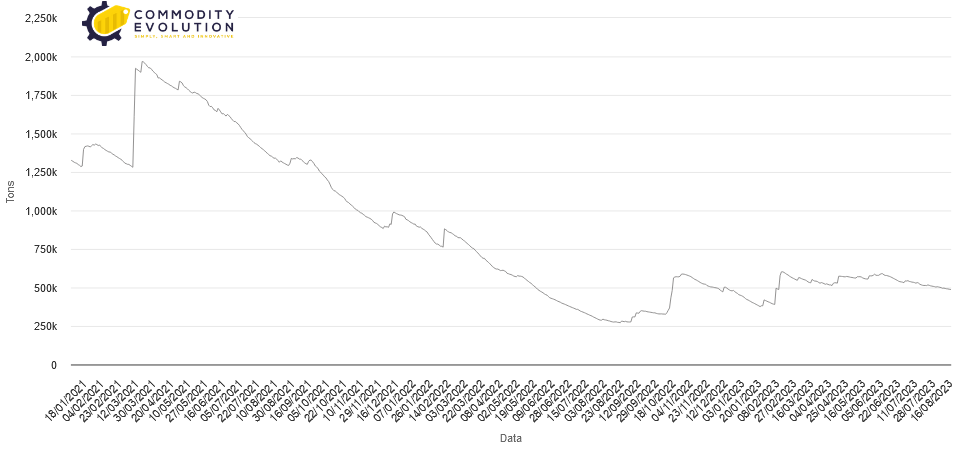

China may consume all the aluminum it produces, but it is unlikely to be able to absorb the surplus. Weak spreads on the LME can be seen, despite low inventories. Low aluminum inventories in warehouses recorded by the LME often fuel concerns about supplies, but not this time.

The spread between the spot aluminum contract versus the three-month contract rose to $55.50 a ton this week, the highest since the 2008 financial crisis. In the United States and Europe, central banks, in an attempt to contain inflation, have raised interest rates, causing industrial activity to stagnate.

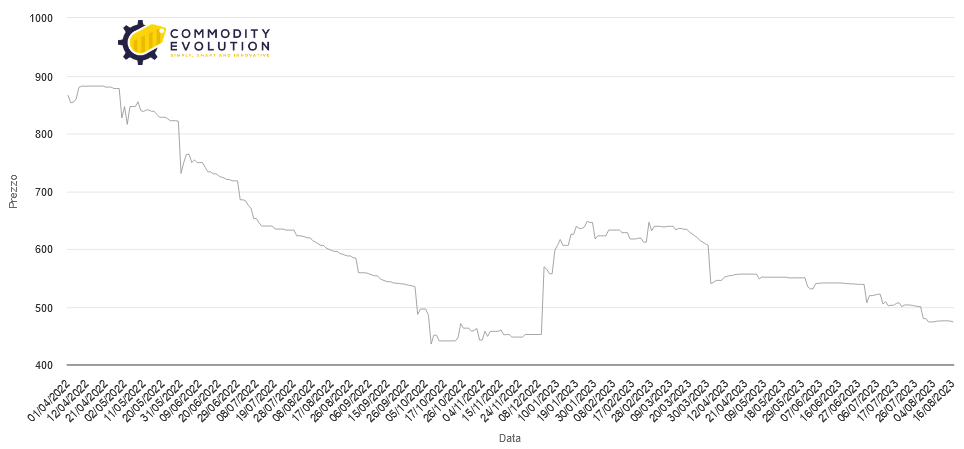

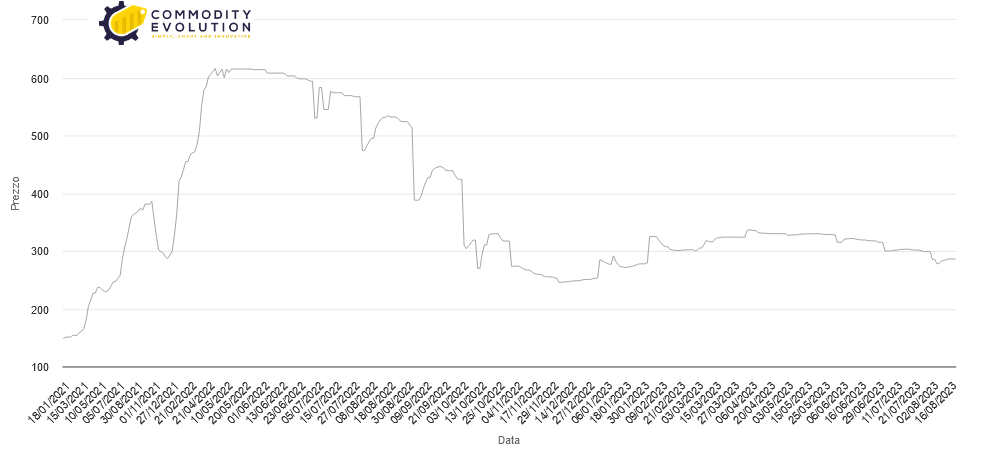

This can be seen in the premiums paid for aluminum in the physical market, which have plummeted. The U.S. premium (U.S. Mid West) stood at $474 a ton, declining 25 percent since mid-March, while in Europe, Aluminum P1020A – DDP Delivered Duty Paid – Holland – Rotterdam was down 15 percent to $286 a ton, partly due to production cuts during the recent energy crisis.

.gif) Loading

Loading