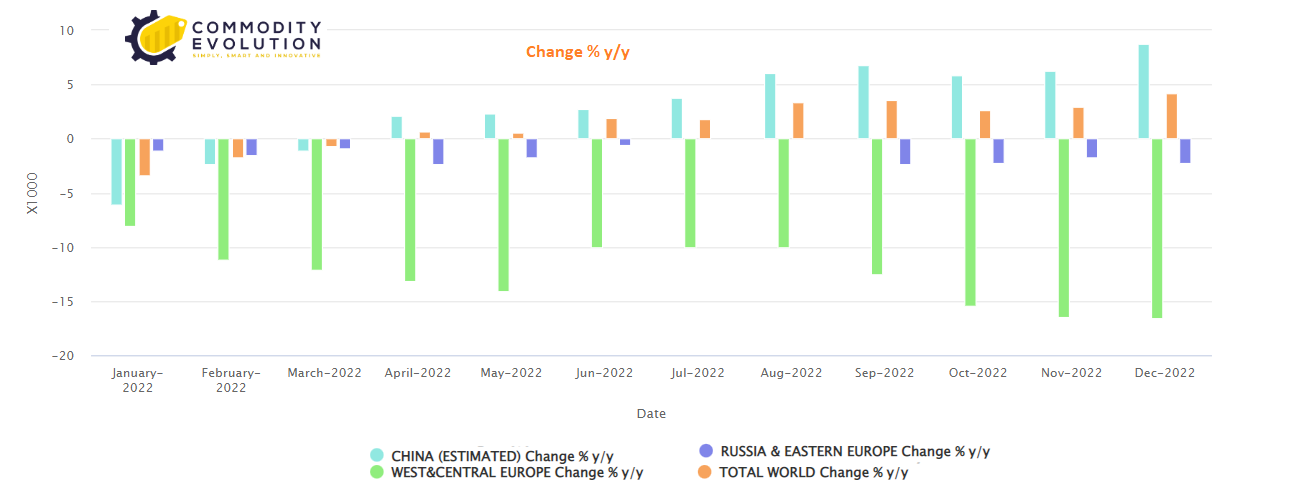

According to the International Aluminium Institute (IAI), global aluminum production increased by a marginal 2.0 percent last year, a growth rate down from 2.7 percent in 2021 and the slowest since 2019. Production barely increased in the second half of the year. Annualized production of 69 million tons in December exceeded June’s overall production rate by just 231,000 tons.

According to the International Aluminium Institute (IAI), global aluminum production increased by a marginal 2.0 percent last year, a growth rate down from 2.7 percent in 2021 and the slowest since 2019. Production barely increased in the second half of the year. Annualized production of 69 million tons in December exceeded June’s overall production rate by just 231,000 tons.

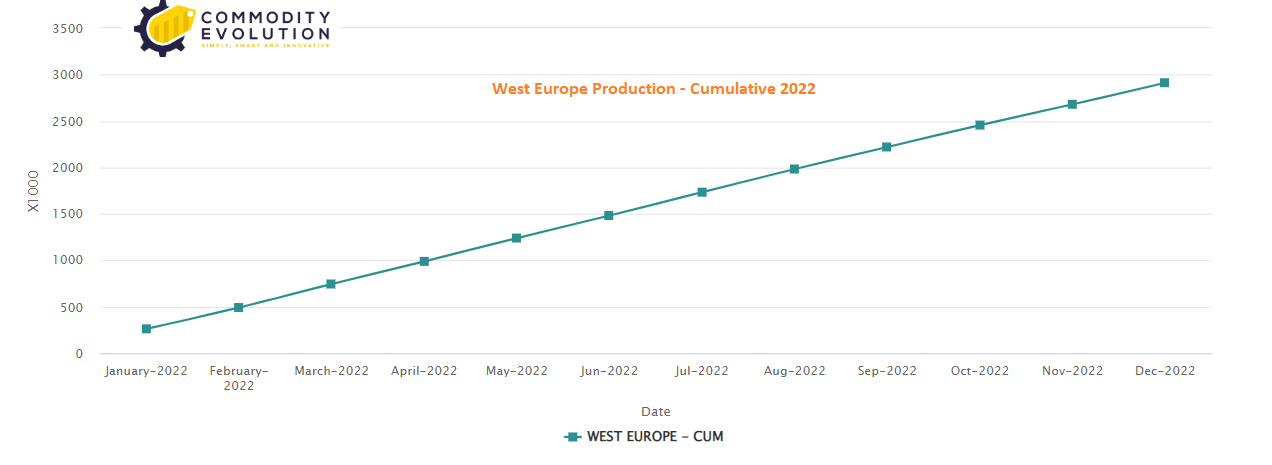

The European energy crisis has taken a heavy toll on a notoriously energy-starved sector. Regional production fell 12.5 percent last year, a major factor behind the 0.9 percent drop in production outside China.

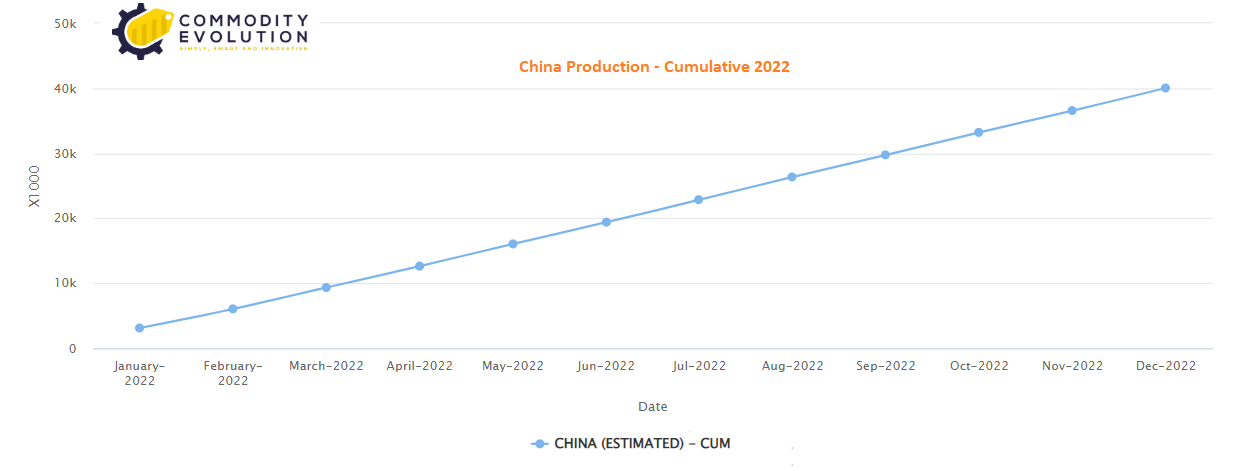

China, the world’s largest producer of primary aluminum, posted 4.0% production growth for the second year in a row.

But it too has been grappling with power problems, most recently in the water-rich provinces of Yunnan and Sichuan. The country’s annual production peaked in August 2022 at 41.46 million tons, but since then production rates have declined by 600,000 tons.

The energy paradox of aluminum is becoming increasingly evident. The production of a metal critical to building a greener energy system is itself increasingly vulnerable to fluctuations in energy availability.

In December, Western European aluminum production was 2.73 million tons year-on-year, down 540,000 tons from December 2021 and the lowest production rate this century.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting surge in electricity prices caused many smelters to shut down and reduce production last year.

The energy crisis in Europe has passed its peak. German base energy for 2024 delivery has fallen from 470 euros/MWh in August to 189 euros/MWh today.

Some European aluminum capacity is coming back. The Dunkirk plant, one of the region’s largest with a capacity of 285,000 tons per year, is reversing 20 percent cuts made in the fourth quarter of 2022.

Slovakia’s only smelter, with a capacity of 175,000 tons per year, has closed all primary operations after 70 years of operation.

The Podgorica smelter in Montenegro closed its last 60,000 tons of primary capacity at the end of 2021. Interestingly, both plants fall under IAI’s Eastern Europe and Russia category. The same is true for smelters in Romania and Slovenia, both of which have drastically reduced operations in the past year.

However, regional production declined only 1.4 percent last year, a counterintuitive result unless the closures were offset by increased production in Russia.

This is possible considering that Rusal was planning to start up its new Taishet plant last year, although there have been no recent updates on the 428,500-ton-per-year project.

China’s production of 40.39 million tons of aluminum last year was a new annual record, but the headline masks significant changes in the country’s network of basic smelters.

In some provinces new production capacity was started and idle capacity restarted, while in others energy restrictions resulted in mandatory reductions for smelter operators.

In some provinces new production capacity was started and idle capacity restarted, while in others energy restrictions resulted in mandatory reductions for smelter operators.

The balance has shifted from rapid growth in the first half of 2022 to declining production in recent months. This year has not seen a repeat of the widespread restrictions imposed during the 2021 winter energy crisis, but the drought in the country’s southwest is weighing on smelters’ operating rates.

According to Shanghai Metal Market, about two million tons of production capacity in Yunnan, Sichuan and Guizhou were out of service by the end of 2022.

It is unlikely to recover until the second quarter, when the rainy season is expected to restore depleted reservoir levels in the region’s hydropower system.

There is still plenty of room for output growth in China, as the government capacity limit of 45 million tons has not yet been reached.

However, the past two years have shown that it is increasingly rare for China to function at its existing capacity for an extended period of time before provincial governments impose energy restrictions of one kind or another to balance energy loads.

It is noted that drought problems in southwest China have not deterred aluminum producers from moving capacity there from coal-fired provinces in search of a metal with a lower carbon footprint.

Pressure toward a greener approach is also becoming a key factor in the rest of the world’s smelter restart. Latin America was the region where aluminum production grew the fastest last year, up 10.7 percent from the previous year.

A key factor was the restart of the Alumar smelter in Brazil, based on a switch to renewable energy. According to 40% owner South32, the restart is taking a little longer than expected, which is not surprising given that the plant last operated seven years ago (read the full news story here).

Alcoa, which holds the 60 percent balance stake in Alumar, also hopes to restart its San Ciprian smelter in Spain after a switch to renewable energy. It has secured two wind energy deals that would cover 75 percent of the 228,000-ton per year plant’s energy needs (read the full news story here).

Slovalco could also be revived by Norwegian owner Hydro if the Slovak government succeeds in implementing the European Union framework on carbon offsets (read the full news story here).

However, the race for renewable energy only exacerbates the aluminum paradox. As more smelters switch to green energy sources, global aluminum production is increasingly dependent on the availability of seasonally variable electricity.

Moreover, seasonality itself is changing, as global warming brings both longer droughts and hotter summer heat waves, which combine to increase energy use and depress energy production.

In recent years it has become clear that China’s aluminum smelters, along with other energy-intensive industries, are the first to be subject to mandatory reductions when a province seeks to balance its grid.

These regional adjustments are now an integral part of the global aluminum production landscape, but they have introduced a new degree of volatility into the previously slow-moving supply side of aluminum.

Moreover, they have raised the possibility that China’s seemingly unstoppable aluminum giant has run out of steam even before reaching the capacity limit set by the government.

.gif) Loading

Loading