The London Metal Exchange will enter 2023 with the lowest inventories in at least 25 years, setting the stage for future pressures and spikes if demand proves stronger than expected.

The London Metal Exchange will enter 2023 with the lowest inventories in at least 25 years, setting the stage for future pressures and spikes if demand proves stronger than expected.

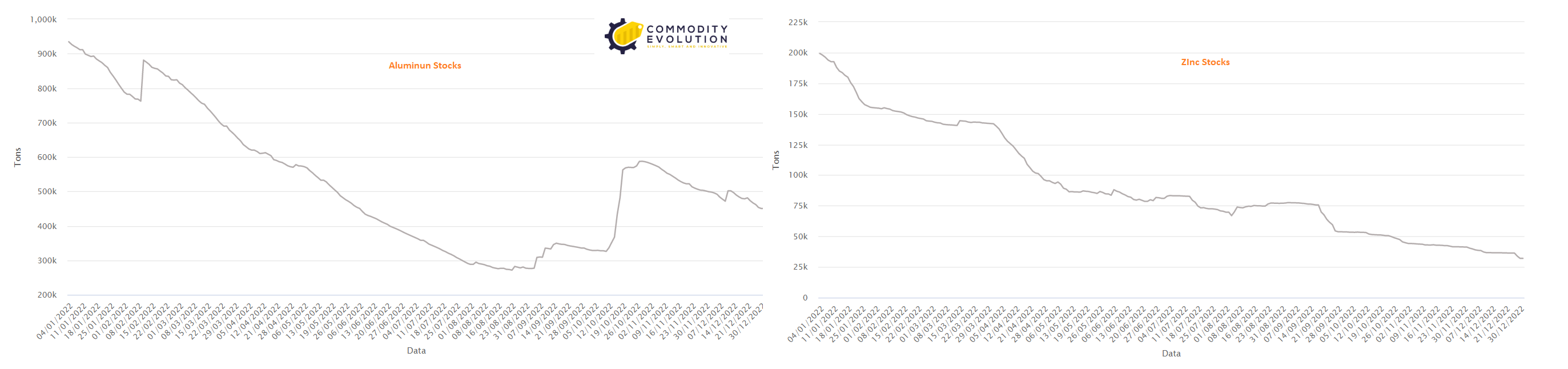

Available stocks of the six major metals traded on the LME fell by two-thirds in 2022, with aluminum down 72 percent and zinc down 90 percent. Overall, stocks not yet marked for withdrawal hit the lowest level in data dating back to 1997 on Thursday and ended the year with only a marginal increase.

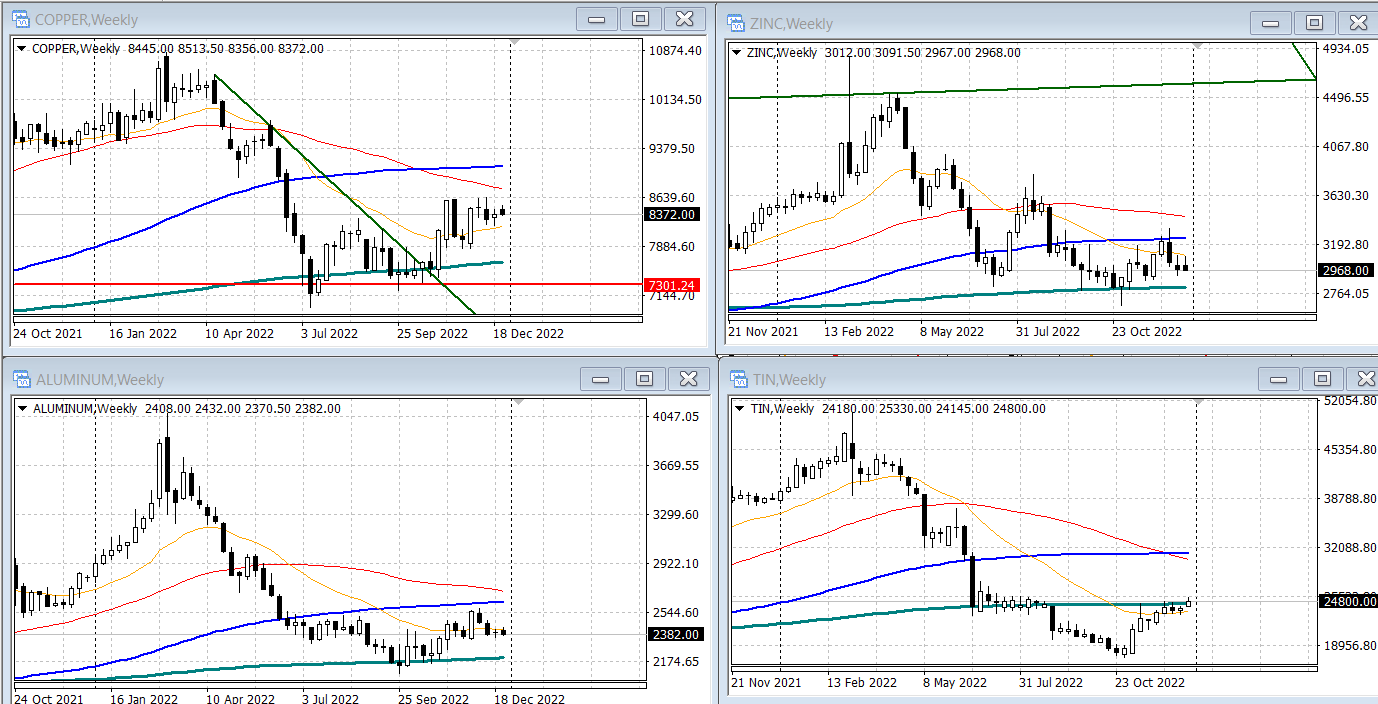

The debate over the supply and demand outlook for metals is particularly contentious in copper, where some analysts predict continued deficits while others see the market swinging toward a rare and historic period of oversupply.

At the end of the year, only nickel was in positive territory. The market continues to be hampered by tight liquidity since the crisis, with periodic sharp swings.

Stock and exchange inventory levels are important because any short seller holding a contract to maturity must deliver the physical metal registered in an LME warehouse. The LME has introduced new rules to allow contracts to be deferred to avoid future pressures, but exemptions carry expensive fees.

The stock shortage also reflects the tension that has gripped metals markets for much of the year, between tight supplies on the one hand and concerns about weakening demand due to recession threats in the world’s major economies on the other.

For LME traders, dwindling stocks are another headache after one of the most dramatic years in the exchange’s 145-year history. The LME is facing regulatory investigations and lawsuits for its actions during the short squeeze in the nickel market in March, which pushed several LME dealers to the brink of insolvency, and will soon release the results of an independent review of the crisis.

Looking ahead to 2023, one of the main debates in the metals markets is whether the global downturn in industrial activity and a recovery in supply will help replenish the sector’s scarce reserves, while China’s recent reopening after the Covid lockout adds further uncertainty.

Copper, zinc and aluminum are down more than 10 percent this year, while tin, the worst, has plummeted by more than a third and is poised to record the largest annual decline since at least 1990.

The historic downturn in the tin market experienced during the early stages of the pandemic has dissipated this year, as demand from the electronics sector has cooled to coincide with a recovery in supply. However, concerns about low inventory levels persist, and prices have rebounded in the past two months as buyers have decided to secure stockpiles in anticipation of a recovery in demand.

.gif) Loading

Loading