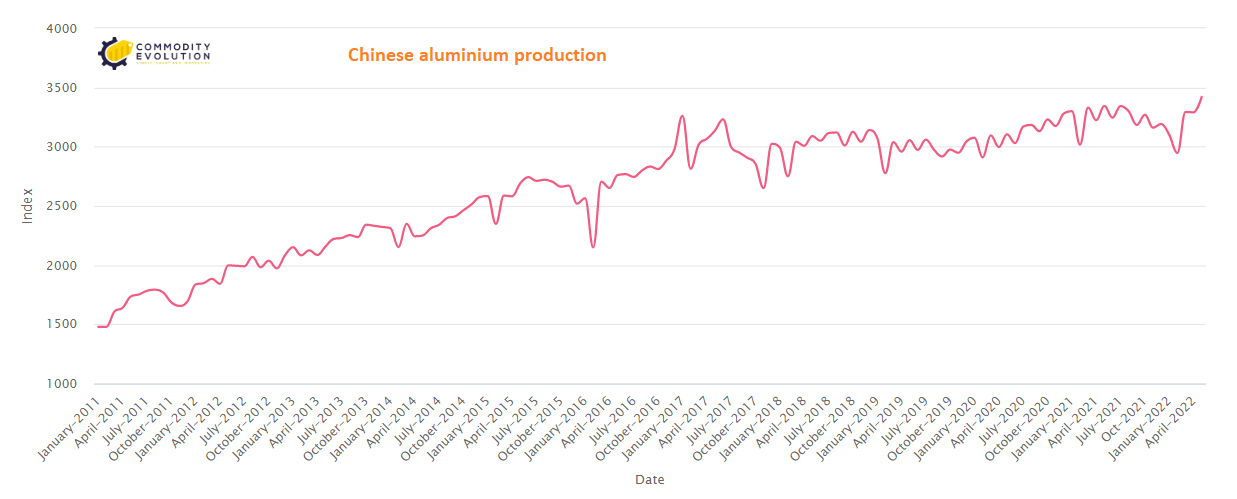

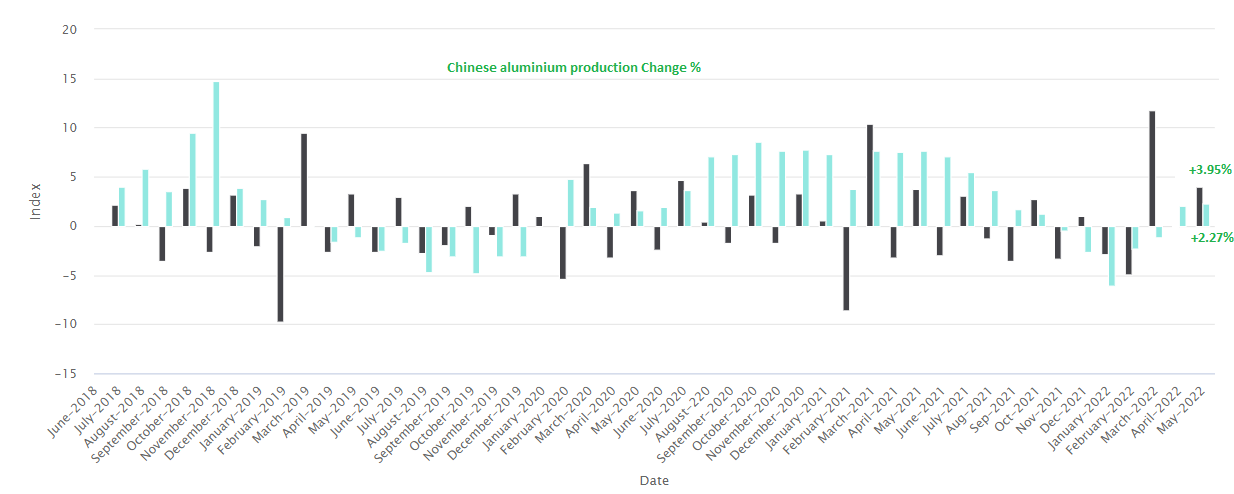

China produced a record 3.42 million tonnes of primary aluminium in May, as the country’s smelters continue to increase production rates.

According to the International Aluminium Institute (IAI), the country’s annual production increased by 3.66 million tonnes in the first five months of the year, culminating last month with the highest operating rate of 40.27 million tonnes.

According to the International Aluminium Institute (IAI), the country’s annual production increased by 3.66 million tonnes in the first five months of the year, culminating last month with the highest operating rate of 40.27 million tonnes.

Chinese smelters are resurging thanks to the easing of the energy crisis that restricted production for much of last year.

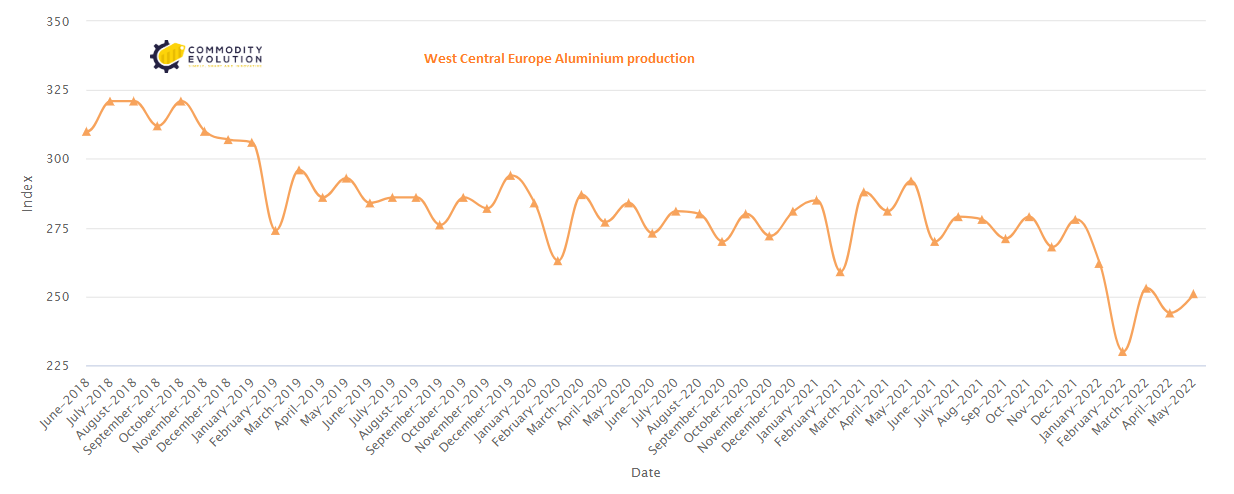

This year it is European smelters that are facing an energy crisis due to soaring electricity prices in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Europe’s energy problems have dragged annual production out of China by 460,000 tonnes this year.

China’s share of global production was 58.91% in May, a ratio that has only been exceeded once before in June 2017, a historical indicator that may be unreliable given the lack of consistent data five years ago.

n this time last year, it was Chinese operators who were struggling with energy supplies for their power-hungry smelters.

Drought in the water-rich Yunnan province, coupled with over-zealous enforcement of energy efficiency targets, caused domestic aluminium production to drop by more than two million tonnes per year by 2021.

These targets were relaxed and China increased coal production to mitigate the energy crisis last year.

Improved electricity prices and strong aluminium prices have generated a predictable rebound in Chinese production rates, which after last year’s pause are again approaching Beijing’s capacity limit of 45 million tonnes per year.

The turnaround in the fortunes of Chinese smelters is evident from the country’s crude metal trade. Imports boomed in 2021 as domestic production failed to meet producers’ demand for primary use. Inbound shipments of primary metal reached a record 1.58 million tonnes.

This year, however, China exported raw metal despite the heavy 15% duty on aluminium exports. Much of what leaves China is bound for Europe, which is now experiencing its own energy-driven aluminium meltdown.

Electricity prices in Europe were already heading north before Russia launched its ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine.

The resulting tightening of gas supplies to Europe has caused electricity prices to soar 400% in the past year, no small problem for aluminium producers, since energy accounts for about 40% of their smelting costs.

The European Aluminium Association claims that around 900,000 tonnes of annual capacity have been impacted in the form of reductions or fluctuations in operating rates.

According to the IAI, annual production in Western Europe has decreased by about 500,000 tonnes over the past year. May’s production rate of 2.96 million tonnes was the lowest this century.

The energy crisis is mainly affecting foundries in Germany, France and the Netherlands, while those in Norway and Iceland have been cushioned by access to hydropower and geothermal energy. The production capacity of both countries has gradually increased over the past year, which probably hides the loss of total production recorded elsewhere in the IAI data on Western Europe.

The energy crisis is mainly affecting foundries in Germany, France and the Netherlands, while those in Norway and Iceland have been cushioned by access to hydropower and geothermal energy. The production capacity of both countries has gradually increased over the past year, which probably hides the loss of total production recorded elsewhere in the IAI data on Western Europe.

Eastern European aluminium production is also declining. Cumulative production fell by 1.5 per cent year-on-year in the first five months of the year, due to reductions in Romania, Montenegro and the Slovak Republic.

The IAI’s latest monthly update shows no sign of a drop in production at Russia’s Rusal, despite the fact that sanctions have interrupted the flow of raw materials to the company’s Siberian smelters.

On the contrary, it is possible that the start-up of the new plant in Taishet is offsetting reductions in the rest of Eastern Europe.

With no end to the current energy crisis in sight, European production could be threatened in the coming months.

An additional 800,000 tonnes of European smelter capacity is estimated to be at risk unless energy prices fall, which seems unlikely at the moment.

Aluminium is not produced by throwing bauxite into a blast furnace. Rather, bauxite has to be refined into alumina, which is then transformed into metal by electrolysis.

Aluminium is in many ways electricity in solid form, which is why smelters are so sensitive to energy prices.

This is a problem for aluminium production everywhere, with smelters competing with other industries for energy, particularly from renewable sources, in an attempt to produce an increasingly ‘green’ metal.

The exponential increase in electricity prices in Europe since the Ukrainian invasion poses an existential threat to many operators in the region.

The need to import a metal that is a key factor in decarbonisation from a country where coal is still the primary source of energy for aluminium production is highly problematic for the European Union.

Not only in terms of carbon footprint, but also in the context of the bloc’s commitment to what it calls ‘strategic autonomy’ in its mineral supply chains.

Chinese smelters are currently enjoying positive margins thanks to a combination of higher metal prices and lower energy costs due to the government’s return to coal utilisation targets.

Despite the coal rush, there are signs of stress in some parts of the Chinese energy system.

Electricity consumption has increased in China’s provinces north of the Yangtze River due to warmer-than-normal weather, so much so that Henan set a new record for peak load demand over the weekend.

The tension on the power grid is set to become more acute as China timidly emerges from the coronavirus freeze and starts to increase production activity again.

If the Chinese summer is long and hot, energy will be prioritised for cooling homes, while large industrial users will face rationing.

The aluminium energy pendulum may have swung back to China from the rest of the world, but it may not stay there for long.

.gif) Loading

Loading