Both nickel and copper possess properties that give them a central role in the drive towards a greener future. While demand will continue to grow steadily, electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage applications will support a huge increase in long-term demand.

Both nickel and copper possess properties that give them a central role in the drive towards a greener future. While demand will continue to grow steadily, electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage applications will support a huge increase in long-term demand.

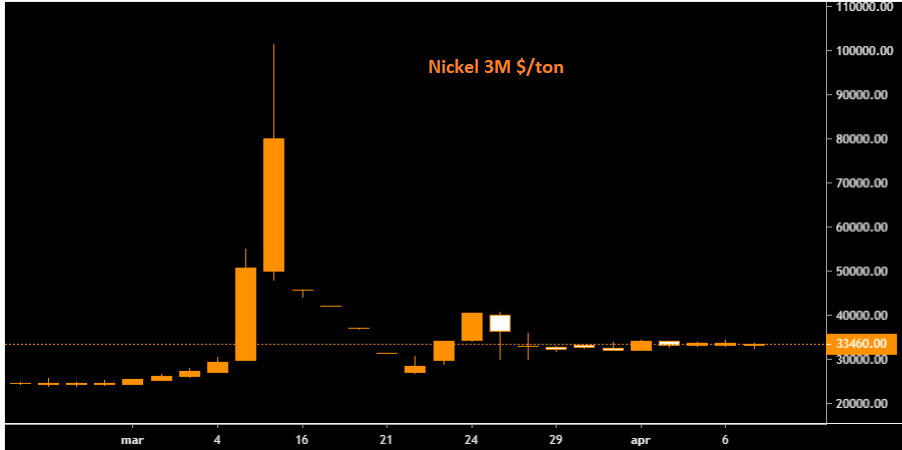

While stainless steel will continue to be the main first use of nickel, the main driver of demand growth over the next two decades will be batteries. From only 7% of the total market in 2021, we expect battery use to grow to 40% of nickel consumption by 2040. This will push demand for nickel to double to six million tonnes per year.

Nickel use in batteries has increased by 900,000 tonnes in the last six months, mainly due to increased net zero commitments by governments and car manufacturers. The growing importance of energy storage to enable wider use of renewable energy will also be an important factor in driving demand.

Forecasts indicate the need to bring an additional 1.65 million tonnes of nickel into production between 2026 and 2038. A further 1.8 million tonnes of nickel will be put on the market between 2011 and 2023.

However, the vast majority of new capacity development over the past decade has been in Indonesia and has had significant environmental side effects. Indonesia’s recent commitments to reverse deforestation and cease coal-fired power plant development would make it extremely difficult to repeat these growth rates.

There is an increasing focus on the use of locally produced raw materials in Europe and the US. However, the lack of new nickel mining development projects outside Asia means that battery manufacturers will have to turn to recycling to fill the gap.

Current projections indicate that 20% of nickel demand for electric vehicles (420,000 tonnes) will be recovered from recycling by 2040.

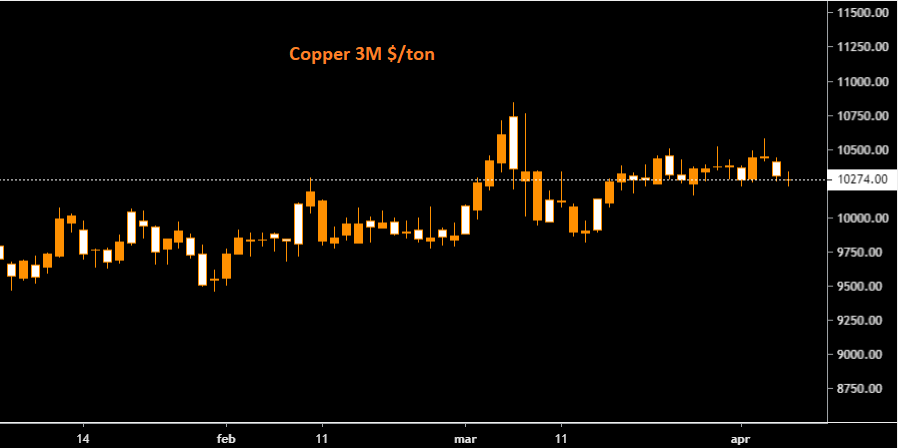

As for copper, its capacity as an electrical conductor will be the main driver of increased demand over the next 20 years and beyond. It is expected that 40% of future demand growth will come from electrical applications in green technologies, including electric vehicles, offshore wind and solar.

Copper’s green credentials are not limited to its role in low-carbon end uses. The carbon intensity of producing finished copper is only a quarter of that of aluminium.

Moreover, most of the copper mining projects planned globally intend to use low-carbon energy sources. In Zambia’s Copperbelt and the Democratic Republic of Congo, energy comes almost exclusively from hydropower. In Chile, up to 50% of the energy used is hydro, wind or solar, with over 90% of new capacity set to be renewable.

Copper and aluminium are interchangeable in many cases, so a lower tax burden for more carbon-efficient copper could make it extremely attractive.

While its ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) profile is good for future copper demand, the current pool of around 2.5 million tonnes of advanced mining projects is lower than a decade ago. This will create a ten-year supply gap of up to five million tonnes until 2031.

As with nickel, given the rapid climb in demand, it is expected that much of future copper requirements will have to be met through recycling. There are signs of significant investment in new processing capacity in North America and Europe, as well as in Asia. This gives confidence that as much as 6 million tonnes of the additional 16 million tonnes of demand over the next 20 years will be met by recycled raw materials.

.gif) Loading

Loading