Zinc on the London Metal Exchange recorded a new all-time high of $4,861 per tonne earlier this month, eclipsing the previous 2006 peak of $4,580 per tonne.

Zinc on the London Metal Exchange recorded a new all-time high of $4,861 per tonne earlier this month, eclipsing the previous 2006 peak of $4,580 per tonne.

The March 8 peak was surpassed within hours and looked very much like the forced closure of positions to cover margin calls in the nickel market, which was imploding at the time before being suspended.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, which Moscow calls a special military operation, has no direct impact on zinc supply, as Russian exports are negligible.

But the resulting rise in energy prices is putting more pressure on already struggling European smelters. European buyers are paying record physical premiums on top of record LME prices, a tangible sign of scarcity that is now beginning to spread to the North American market.

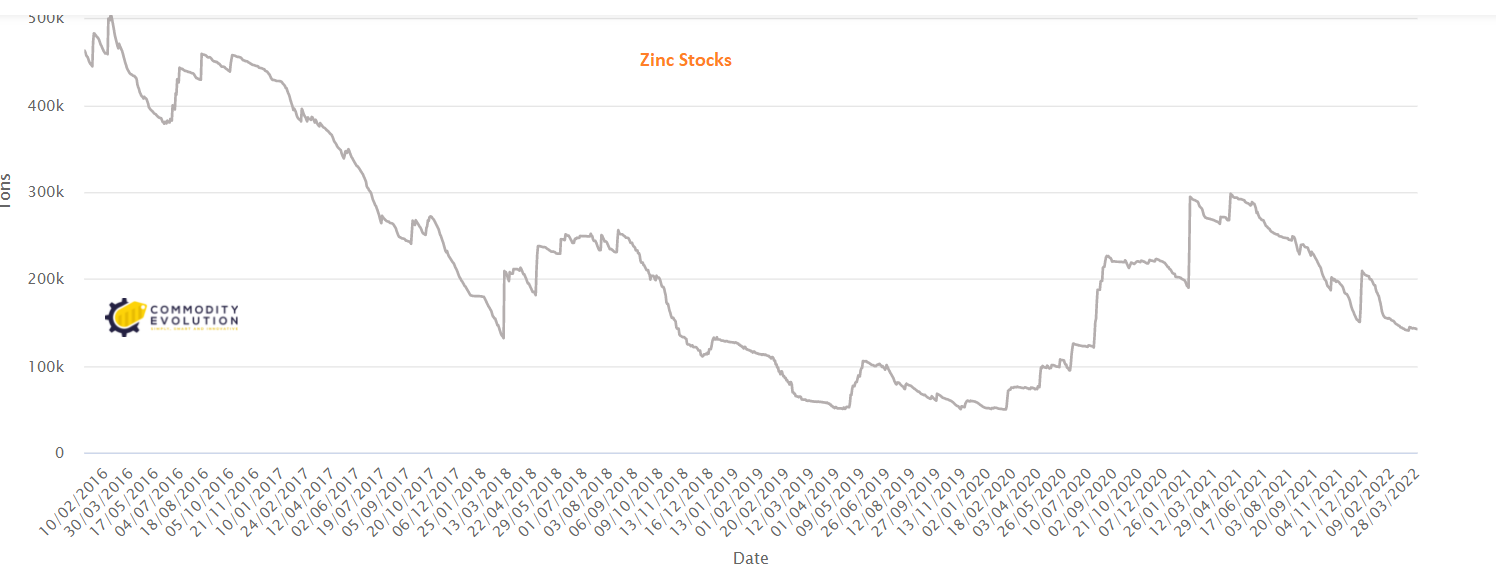

The world is not yet running out of metal but a market that until a few months ago was expected to be in oversupply now seems to be changing.

Auby’s Nyrstar plant in France has returned to partial production after being shut down in January due to rising energy costs. But operating rates at the three European smelters, with a combined annual capacity of 720,000 tonnes, will continue to be reduced with total production cuts expected of up to 50%.

Clearly high electricity prices in Europe mean that it is not economically feasible to operate the sites at full capacity. In ‘care and maintenance’ is Glencore’s 100,000 tonne per year Portovesme site in Italy, another victim of the energy crisis.

Zinc smelting is an energy-intensive business and these smelters were already in trouble before the Russian invasion sent electricity prices in Europe even higher.

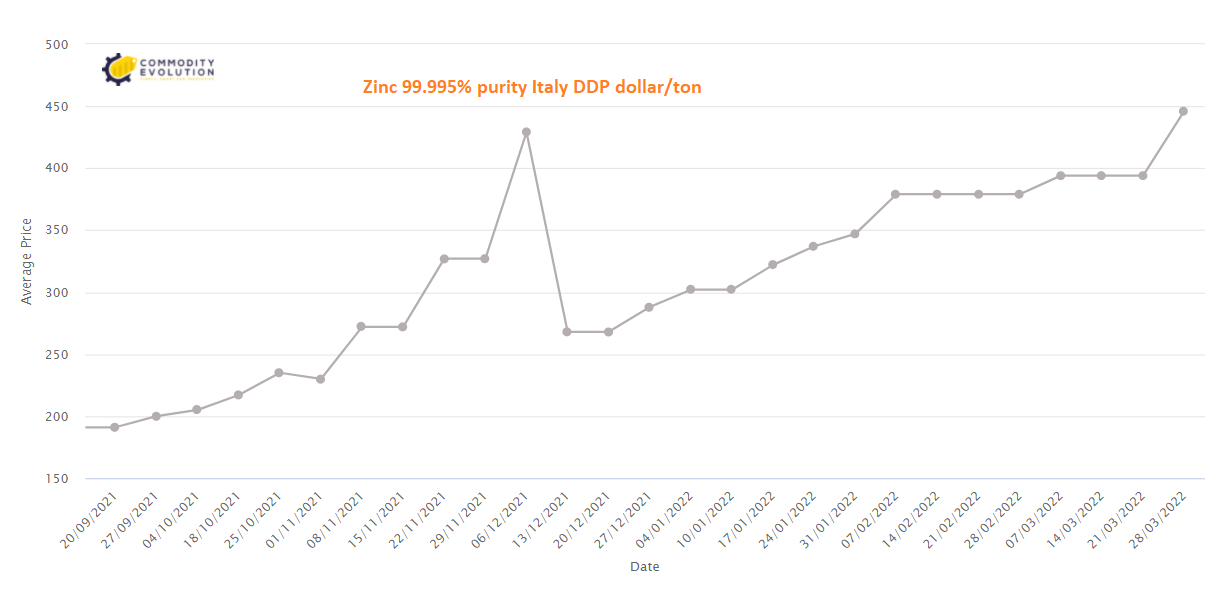

Record physical premiums, paid on top of the LME cash price, attest to the regional shortage of the metal. The premium for special grade zinc at the Belgian port of Antwerp rose to $450 a tonne from $170 last October, before the winter heating crisis hit.

The Italian premium exploded from $215.00 to $462.50 per tonne over the same period.

LME warehouses in Europe hold only 500 tonnes of zinc – all at the Spanish port of Bilbao and almost all of the 25 tonnes cancelled in preparation for physical loading.

LME stocks in the United States amount to 25,925 tonnes and the available tonnage is even lower at 19,825 tonnes. Last year at this time, New Orleans alone had nearly 100,000 tonnes of zinc.

About 80% of the LME’s zinc inventory is now in Asian locations, with Singapore holding 81,950 tonnes.

There is also a lot of metal in the Shanghai Futures Exchange’s warehouses. Registered stocks saw the usual seasonal surge over the Lunar New Year holiday, rising from 58,000 tonnes at the beginning of January to 177,826 tonnes today.

There is also a lot of metal in the Shanghai Futures Exchange’s warehouses. Registered stocks saw the usual seasonal surge over the Lunar New Year holiday, rising from 58,000 tonnes at the beginning of January to 177,826 tonnes today.

Clearly Asian buyers have not yet been affected by the impending supply crisis in Europe and there is much potential for a wholesale redistribution of stocks from East to West.

This is what happened last year in the lead market, China exported its surplus to help fill gaps in the western supply chain. Lead, however, should also serve as a warning that global rebalancing may be a slow and protracted affair due to continued blockages in the shipping sector.

The European continent accounts for about 16% of global refined production and the loss of production due to the regional energy crisis has disrupted the zinc market.

When the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG) last met in October, it predicted a global supply surplus of 217,000 tonnes for 2021. This was already a sharp reduction from its previous assessment in April of a 353,000-tonne production surplus.

The group’s most recent calculation is that the projected surplus turned into a deficit of 194,000 tonnes last year. The difference was almost entirely due to lower-than-expected growth in refined production, which was only 0.5% compared to an October forecast of 2.5%.

With Chinese smelters recovering from their power problems earlier in the year, the deceleration in the fourth quarter was largely due to lower production rates at European smelters. The extent of the upward shift in energy prices, not only at spot but across the entire forward curve, poses a long-term question mark over the profitability of European zinc production.

.gif) Loading

Loading