Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is raising the price of metals used in cars, from aluminum in bodywork to palladium in catalytic converters to high-grade nickel in electric vehicle batteries, and drivers are likely to foot the bill.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is raising the price of metals used in cars, from aluminum in bodywork to palladium in catalytic converters to high-grade nickel in electric vehicle batteries, and drivers are likely to foot the bill.

While metals have not yet been the target of Western sanctions, some shippers and auto parts suppliers are already turning away from Russian goods, putting more pressure on automakers already reeling from a chip shortage and higher energy prices.

According to Carlos Tavares, CEO of Stellantis, the world’s fourth largest auto manufacturer, what’s happening is that you have a cost escalation coming from raw materials and energy that is going to put more pressure on the business model. Tavares reported that an end to the chip shortage could help automakers offset rising metal and energy prices, but he doesn’t expect a resolution to the semiconductor problems this year.

Andreas Weller, CEO of Aludyne, which makes aluminum and magnesium die-cast parts for automakers, reported that his European business has seen a 60% increase in the cost of aluminum over the past four months, as well as rising energy bills.

With annual sales of $1.2 billion and a cost hike of “hundreds of millions of dollars,” Weller, whose company is based in Southfield, Michigan, reported that it has been forced to ask customers to pay more than the prices already agreed upon.

German automakers such as Volkswagen and BMW have already been hit by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has forced wiring harness manufacturers in the west of the country to halt production. A wiring harness is a vital set of parts that neatly bundle up to 5 km (3.1 miles) of wiring in an average car, and Ukraine is a key supplier.

And when it comes to metals, Russian companies are Germany’s top suppliers. In 2020, they accounted for 44% of Germany’s nickel imports, 41% of titanium, a third of iron and 18% of palladium.

With production of 108 million tons last year, Russia is the world’s fifth-largest producer of iron ore and supplies European steel mills, which now face higher prices and possible difficulties sourcing the metal.

Faced with the choice of buying Russian assets and indirectly financing the invasion of Russia, which Moscow calls a special military operation, German steel and aluminum supplier Voss Edelstahlhandel has decided to stop sourcing from Russia.

“Even though aluminum is not on the sanctions list, it is used by Russia to get money into the country and so we have stopped,” CEO Thorsten Studemund told Reuters.

Russia is a large producer of aluminum, the most energy-intensive metal to produce, accounting for 6 percent of global output.

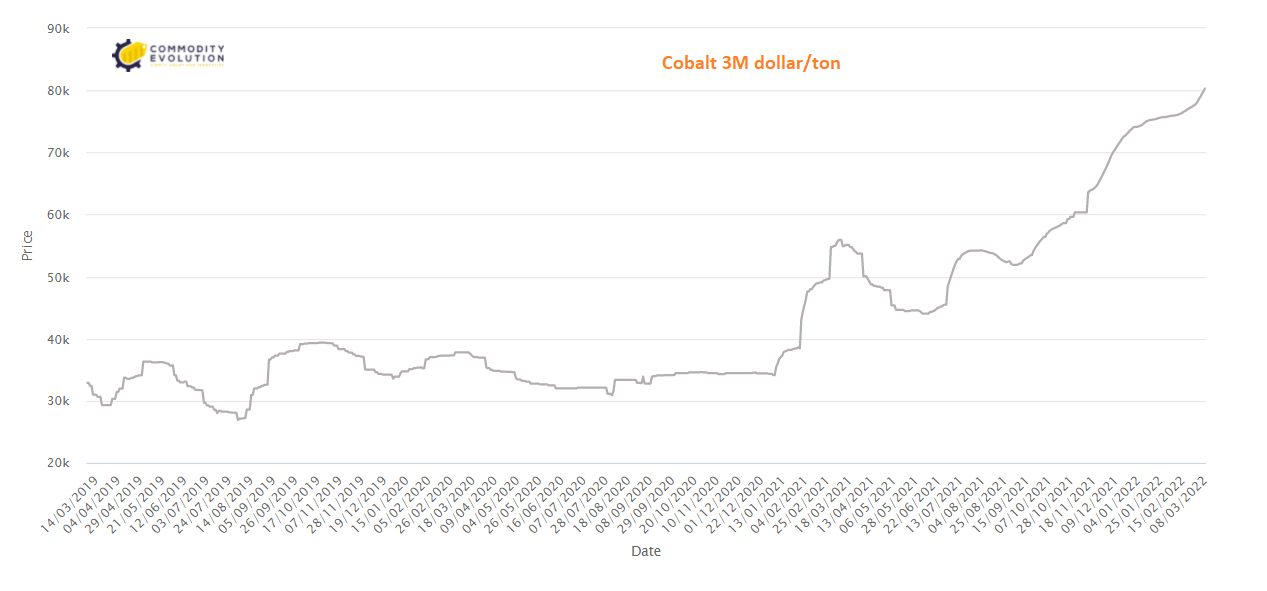

Studemund’s company has also been grappling with high nickel prices. The metal is used to make batteries for electric vehicles (EVs), posing a new challenge for automakers already investing billions to move away from combustion engines just as demand for zero-emission models is starting to take off.

Some of Russia’s high-grade nickel will likely end up in China, which is unlikely to impose sanctions on Russia, but this all comes at a time when automakers are facing increased spending on other EV battery minerals as demand outstrips supply.

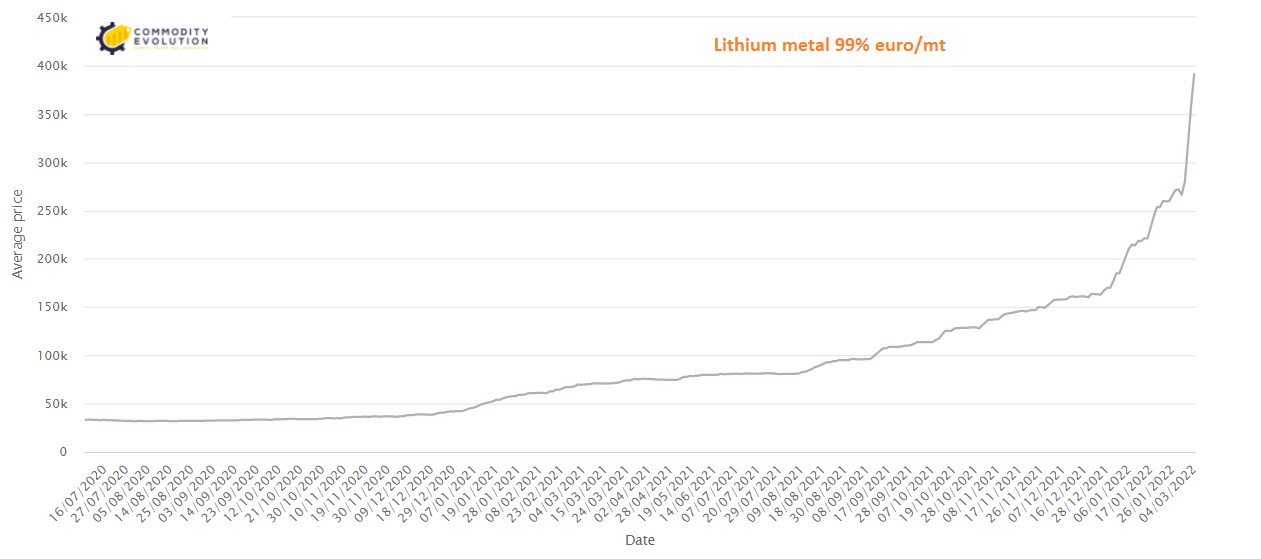

This is the main concern for the battery supply chain, as you have record prices for lithium and very, very high prices for cobalt and nickel.

Batteries are one of the most expensive components in electric vehicles, and automakers are hoping they will become cheaper so they can offer more affordable electric cars.

BMW reported that it was focusing as much as possible on recycling battery nickel, with up to 50% scrap nickel used in the high-voltage battery.

For palladium, automakers are also struggling. The auto industry uses it in catalytic converters for gasoline models – or platinum for diesel models – both of which still make up the vast majority of car sales. Palladium prices have been rising for about six years, and Russia accounts for about 40 percent of the global market.

There is no other option besides palladium and platinum for catalytic converters, and you can’t build a car without a catalytic converter. It is estimated that the palladium used in an average car is about $200, but that could easily double. Either consumers will pay more for cars, or if automakers can’t pass it on, they’ll have to find cost savings somewhere else.

.gif) Loading

Loading